Graffiti on a USAID sign in the occupied West Bank, 2007. Photo by David Lisbona

In 1961, President John F. Kennedy launched the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) by executive order. His stated purpose was to advance global economic development lest “poverty and chaos lead to a collapse of existing political and social structures which would inevitably invite the advance of totalitarianism into every weak and unstable area.” Sixty-some years later, JFK's nephew Bobby Kennedy Jr. described the government's foreign-aid organization as a “sinister propagator of totalitarianism.”

Poles apart, these descriptions, but the recent shuttering of USAID reveals a decades-long wrangle over the use of foreign aid in the pursuit of politics. I remember it well...

The West Bank was silent. The rain did that, muffling the sound of Abu Hanna's van as he droned on the road south of Hebron. He chatted nervously with a friend from Jerusalem. Today was trouble.

The van skirted the southern edge of the stormcloud canopy and headed into the mountains. Dozens of villages ornamented the hills like unpolished stones in an earthen mosaic: ruddy earth, green grazing grass, dark scrub and olive trees, thick and gnarled in lines along the terraced hillsides. The wadis, usually dry riverbeds, now nursed fields of barren apple and plum trees. Grapevines crawled across the ground like outstretched hands.

Today was trouble. Abu Hanna parked across the muddy road from the village council building. Villagers arrived, sitting in a circle of chairs in a small, turquoise room while a boy in a yellow beanie brought around a tray with glasses of tea. The elders wore skirted suits and white headdresses, squeezing prayer beads and taking tea. The young men with uncovered heads wore bell-bottomed pants and muddy dress shoes. There were no women in the room.

Abu Hanna was silent. He had to be. He helped coordinate agricultural aid projects on the West Bank for a private American humanitarian agency, the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC). Every word was a potential political grenade tossed into the room, part of an almost 80-year-old war between Palestinians and Israelis. Abu Hanna – known formally as Ibrahim Mater – decided it was more important to improve the lot of villagers than to confront Israeli occupation. The only thing his colleague from the Mennonite Central Committee got by testifying to Congress about Israeli settlers trampling on Palestinian land and water rights was being banned from the West Bank.

It was 1980. I was there, fresh out of journalism school, bouncing around the Middle East in hopes of filing dispatches for Rolling Stone or Mother Jones. Or working with the Jerusalem bureaus of the Washington Post or Time magazine. Those were tricky times, as every story going back home via telex (there was no Internet) had to be approved by Israeli military censors. I wanted to write about how the Israeli military had sandbagged Abu Hanna, leaving these villagers feeling betrayed.

In traditional Arab agriculture, olive trees take 10 years to mature and fruit. Most farmers rely on ancient orchards, not able to make long-term investments in new trees. Months ago, the AFSC promised to deliver hundreds of seedlings if the farmers would set aside and plow large areas of land for the planting. Now, the Israelis slapped a stop-order on seedling distribution and the nursery, in a panic, sold the promised trees to farmers in Israel proper. The West Bank villagers would have to wait another year.

I started my journalistic sojourn in the Middle East with a volunteer stint at Kibbutz Yad Mordechai, one of the last Israeli enclaves on the road to Gaza. A statue of Mordechai Anilewicz grasping a grenade welcomed tourists to the little museum kibbutzniks had built.

Charity good, development bad

When Abu Hanna proposed to Israeli authorities to get U.S. food surpluses to Palestinian refugees, permission was granted. Hebron needed a hospital for the deaf. Permission granted. Beit Jala wanted a kindergarten, farmers near Wadi Qura needed a road, the Jenin Ladies Red Crescent requested industrial knitting machines – permissions granted.

But when Palestinian farmers asked to dig new irrigation wells, permission was denied. Villages where the Israelis provided electricity only at night wanted a day-time generator to establish light industry – permission denied. The Arab College of Medical Science requested to open a masters program in public health… permission denied.

Abu Hanna helped replace caved-in flatroofs down in Gaza with asbestos-reinforced concrete. The roofs stopped leaking, but he felt ashamed that all they could do was put a roof over a 100-year-old woman sleeping in rags on the floor. What Gaza really needed was a major slum-rehabilitation project, he said, and small business loans without prohibitive interest rates. Palestinians needed to establish cooperatives for economic development – the Israelis had approved only 10 out of 150 applications.

Procedures from the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs, enforced by the military governor, gave Israelis total oversight of every aid project at every stage of development. Most of Abu Hanna's proposals were never denied – just delayed indefinitely. If he worked too closely with the villagers, he would arouse Israeli suspicions. If he tried to please the military, he lost integrity with the people, all living under a military government they neither choose nor wanted.

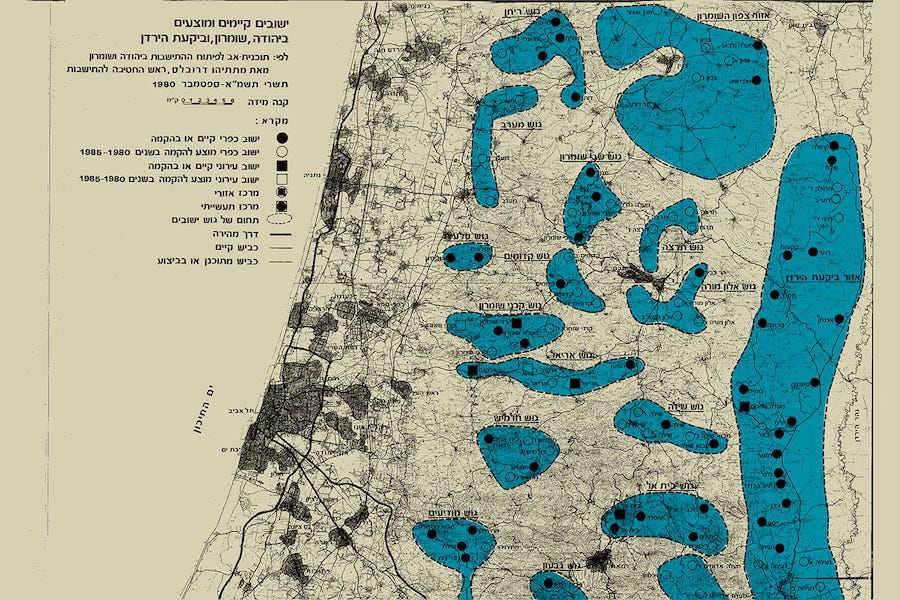

The patterns of micro-management led Abu Hanna to believe the overlords wanted the West Bank economy dependent on Israel, where 80,000 Palestinians commuted to work. Israelis wanted export markets for their goods, not a self-reliant West Bank. Humanitarians with big ideas about Palestinian independence were pressed to trundle off to another Third World country. After all, the game plan from the World Zionist Organization was to gradually de-Arabize the West Bank and Gaza, Abu Hanna said. He showed me the map. Israeli settlers would systematically ring the existing Arab villages and make life so miserable, the Arabs would just pack up for Jordan or the UAE.

Strings, firmly attached

What Abu Hanna and sources with American Near East Refugee Aid, Amideast, Community Development Fund and a dozen other aid organizations reported was how U.S. foreign aid dollars – funding from USAID to non-profits – were subject to political tests. Eclipsing the merits of a project was who would benefit. Brig. Gen. Binyamin Ben-Eliezer, the military governor of the West Bank at the time, told the New York Times that too many aid workers “make always with the radicals, with the nationalists and with those who always will be against the military government.”

By 1994, the year the Palestinian Authority had been promised exclusive control in Palestinian urban areas, USAID bypassed the non-profits and opened an official mission for the West Bank and Gaza – with offices not in the Occupied Territories but in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv. The stated goal was an honorable-sounding partnership with the Palestinian people “to promote prosperity, peace, and opportunities.”

That rocky partnership, however, ended in 2019, when the Palestinian Authority believed President Trump was twisting its arm to accept defeat on a two-state solution. USAID pulled out, abandoning a nearly complete multimillion-dollar sewage system in Jericho and a $1.4-million school under construction near Bethlehem (aid was restarted in 2021 under President Biden).

The litmus test of whether aid recipients support or oppose U.S. policies has plagued Latin America for decades. In 2012, Venezuela, Cuba, Ecuador and other left-leaning countries expelled USAID from their countries. Cuba had discovered that USAID ran a covert Twitter-like service to spark a “Cuban Spring” opposed to the island's Communist government. The next year, Bolivia expelled USAID personnel, claiming they were conspiring against the government of Evo Morales, the country's first and only indigenous president. He survived a recent assassination attempt and hopes to run for president again next year.

Samuel Gompers, one-time president of the American Federation of Labor, is attributed with the political maxim of “rewarding our friends and punishing our enemies.” Is that what John F. Kennedy would do?