The Resurrection of Jesus was a “false flag operation,” right? According to the New Testament, the Jewish hierarchy that plotted his assassination didn’t want any talk of miracles. They paid the men guarding the tomb – guards employed by the temple, not the Romans – to blame the mysterious disappearance of Jesus’ body on his disciples.

Or was it a hoax - the disciples spirited away Jesus’ body and launched a disinformation campaign with the story of paid-off guards?

While the New Testament is viewed as biography vested with belief and bias, few historians seriously deny that Jesus of Nazareth actually existed. There are enough extrabiblical references to Jesus to conclude he was not the fiction of a few delirious disciples.

Popular Jewish historian Max Dimont goes so far as to call Jesus the most significant figure in Western history.

“Whichever view one accepts – Jesus as Son of God, as a prophet or as a Hebrew sage – one thing remains indisputable,” Dimont writes in Appointment in Jerusalem. “Jesus is the central personality in a remarkable trinity: Moses, Jesus and Paul – a trinity that gave birth to Western Civilization.”

Jesus didn’t dot down one word that we know of and he was executed by the Roman government for preaching treason against Caesar after, at most, three short years of public ministry. Some 2,000 years later, it’s a miracle we even know he existed. That miracle has been called “the Resurrection.”

Four Stories

The early Christians said their leader rose from the dead, a claim unique to Christianity. The Apostle Paul wrote, years later, that if Jesus has not been raised, the Christian religion is “useless” (I Corinthians 15:14).

Can anyone seriously believe such a claim? What other options exist for the history-minded? How would an investigative journalist report on arguably the most mysterious man who ever walked this world?

The New Testament gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John tell four different versions of the resurrection story. These accounts are wildly different - at the same time, they share several key elements: Jesus is quickly buried by Joseph of Arimathea because the Sabbath is approaching; women disciples come to the tomb Sunday morning to complete the burial process; they find the tomb empty. Jesus appears to his male disciples separately.

Upon this skeleton of a story, details are hung differently by the different writers. Clearly, none of Jesus’ followers claim to have seen him exit the tomb and various versions of subsequent events circulated around the earliest Christian community.

After studying the Jewish origins of Christianity in Israel for the better part of a year, I concluded that Luke’s gospel is the most Hebraic – it reflects myriad nuances of Jewish culture in the First Century. Contrary to most modern scholarship, I further concluded that John’s gospel was an attempt by Jesus’ youngest disciple to set the historical record straight in his elder years.

Matthew and Mark seem to rely heavily on other sources and contain many misunderstandings of First-century Jewish life and thought. (I touched on this in Part I of this article while dissecting the so-called Trial of Jesus – Luke and John record a rabbinic interrogation while Matthew and Mark depict an irregular, if not illegal, courtroom drama).

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem

Consider how the four resurrection stories play out:

Jesus’ body is removed from the cross by Joseph of Arimathea, a respected leader in the Jewish court. If Jesus is left on the cross, he will be considered cursed under Jewish law (see Deuteronomy 21:22-23) and thrown into a common grave for criminals.

Because of Jewish Sabbath laws, the burial of Jesus takes at least two phases. A full-scale, mummy-style interment (like that given to Jesus’ friend Lazarus in John 11:44) is not possible because work must cease at sundown on the Sabbath. Joseph starts the burial process, while Jesus’ female disciples take careful note of which tomb the men lay him in so they can finish the job after the Sabbath.

John alone mentions a burial with 75 pounds of spices. This indicates to some scholars that Jesus may have been in the tomb three days and three nights, instead of the day-and-a-half allotted by church tradition, and that the mummification took place between a Thursday Passover and the regular Saturday Sabbath.

Regardless of the burial process, the gospels agree that on Sunday morning, Mary Magdalene and other women go back to the tomb. In Luke, the women find an empty tomb and two men in “clothes that gleamed like lightning,” who tell them that Jesus has risen just as he foretold in Galilee (Lk. 24:4-8).

They locate the Eleven apostles, who do not believe their story. Peter alone goes to check the tomb, but leaves confused.

Mark writes that the women find one young man in a plain white robe sitting inside the tomb. He instructs them to tell Peter that Jesus will meet them all in Galilee, but the women are afraid to tell anyone.

Matthew’s account is the one suitable for special-effects fans. Here, an angel causes a violent earthquake by swooping down from heaven, rolling the stone to the cave aside and sitting on it. He instructs the women to tell the disciples to meet Jesus in Galilee, and then Jesus himself appears to them to confirm the angel’s words. The Eleven don’t see Jesus until they rendezvous at a Galilean mountain (Mt. 28:16).

John’s gospel gives a completely different account of what Mary Magdalene and Peter saw. Here, Mary finds the empty tomb and immediately goes to tell the apostles. Peter and “the other disciple” (like “this reporter,” John never refers to himself by name) run to the tomb to see for themselves.

They see the “strips of linen” – possibly hardened into a body-shaped shell – and “believe.”

Mary apparently comes in third place, arriving back at the tomb after the men are gone. She speaks with two angels sitting in the tomb and then meets Jesus, whom she does not recognize at first. Jesus instructs her to tell the other disciples. That night, Jesus appears to most of the disciples, a week later to Thomas, and even later while the disciples are fishing in Galilee.

These and numerous other discrepancies in the Bible have gnawed at Christians since the Second Century, but not enough to lead the church to scrap Matthew, Mark, Luke and John and concoct a single, unified narrative. The gospels have been preserved with all their mysteries because the bones of Jesus have never been found.

Whatever happened that first Easter completely transformed the apostles from cowering fugitives to world conquerors.

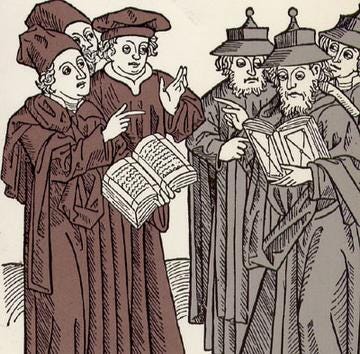

Scholars debate in 15th-century woodcut by Johann von Armssheim

Seven Theories

Around 170 A.D., a Greek philosopher named Celsus wrote a book to discredit the claims of the early church. Although not a scrap of his True Doctrine has survived to modern times, we know some of what he had to say because a Christian writer, Origen, penned a surviving eight-volume rebuttal called Against Celsus.

Celsus wrote that the New Testament record of Jesus’ miraculous life was simple mythology, written by people who believed in him. Celsus attributed the resurrection story to “a hysterical female, as you say, and perhaps some other one of those who were deluded by the same sorcery.”

The theory that the empty tomb was a dream or hallucination is only one of at least six alternate explanations for the Resurrection. Given we have no body, bones or other empirical evidence to study scientifically, it is up to the individual to decide whether or not one of these is more believable than the Christian narrative of a risen Lord.

1. The Resurrection was a faith event. Similar to Celsus’ dream/hallucination scenario, this one suggests that the Resurrection was an internal vision of faith and was never meant to be construed as a physical/historical event. The Gnostic Gospels, dating from the early Second Century, claim that Jesus was a wholly spiritual entity, not a human being subject to pain and death.

For Gnostic Christians, personal mysticism – not official church pronouncements – was the key to understanding Jesus. Many modern Christian scholars advance some version of this, saying the power of the Resurrection lay in Peter and the apostles’ eschatological vision, not in an empty tomb.

2. The disciples took the body. As previously explained, Matthew records that for some time, a story had been circulating that Jesus’ disciples had taken his body and promoted a hoax. The origin of this conspiracy theory, he writes, was the very Jewish priests and elders who had arranged for Jesus’ execution and, further, posted a guard at the tomb to prevent such a hoax (Mt. 27:64-66).

This theory found new followers among the German Bible critics of the 1700s. Herman Samuel Reimarus described the disciples as plotters in a Resurrection hoax in The Goal of Jesus and His Disciples.

3. The wrong tomb. In 1907, British New Testament scholar Kirsopp Lake wrote that the women simply went to the wrong tomb that first Easter Sunday. Perhaps Joseph of Arimathea misplaced Jesus’ body and didn’t correct the misunderstanding.

4. The double tomb. In a variation on this theme, French theologian Guillaume Baldensperger speculated in 1932 that there were two tombs – the one where Joseph of Arimathea put Jesus for the quick, first phase of the burial and a second one where he secretly reburied Jesus without telling the disciples. Not knowing this, the women found the tomb empty and proclaimed the Resurrection.

5. The chief priests took the body. St. Paul seems under the impression that it was not Jesus’ followers who buried him. In the Book of Acts, the sequel to Luke’s gospel, Paul tells a group of Jews in Syria that “the people of Jerusalem and their rulers” were the ones who asked Pontius Pilate to execute Jesus, took him down from “the tree” and buried him (Acts 13:27-29). This theory should probably include an explanation for why the Jews or Romans didn’t just produce the body they’d stolen and quash the Resurrection fable before it started.

6. Jesus survived the crucifixion.The Jewish historian Josephus wrote shortly after the time of Jesus that men did, on occasions, survive crucifixion. The Quran embraces a version of this theory, stating that it was Judas – not Jesus – who died on the cross.

A modern variation was proposed in 1965 by Jewish scholar Hugh Schonfield. The Passover Plot uses New Testament texts to indicate that Jesus – not Peter and the disciples – engineered the Resurrection by only appearing dead, secretly resuscitated in Joseph’s rock-hewn tomb.

Historians, journalists and conspiracy buffs are still wrangling over who killed President John F. Kennedy in 1963. It’s even harder to determine what really happened to Jesus at the dawn of the Common Era. People have found numerous ways to follow him or explain him away. Eventually each of us will find out whether or not resurrections happen.

Happy Easter!