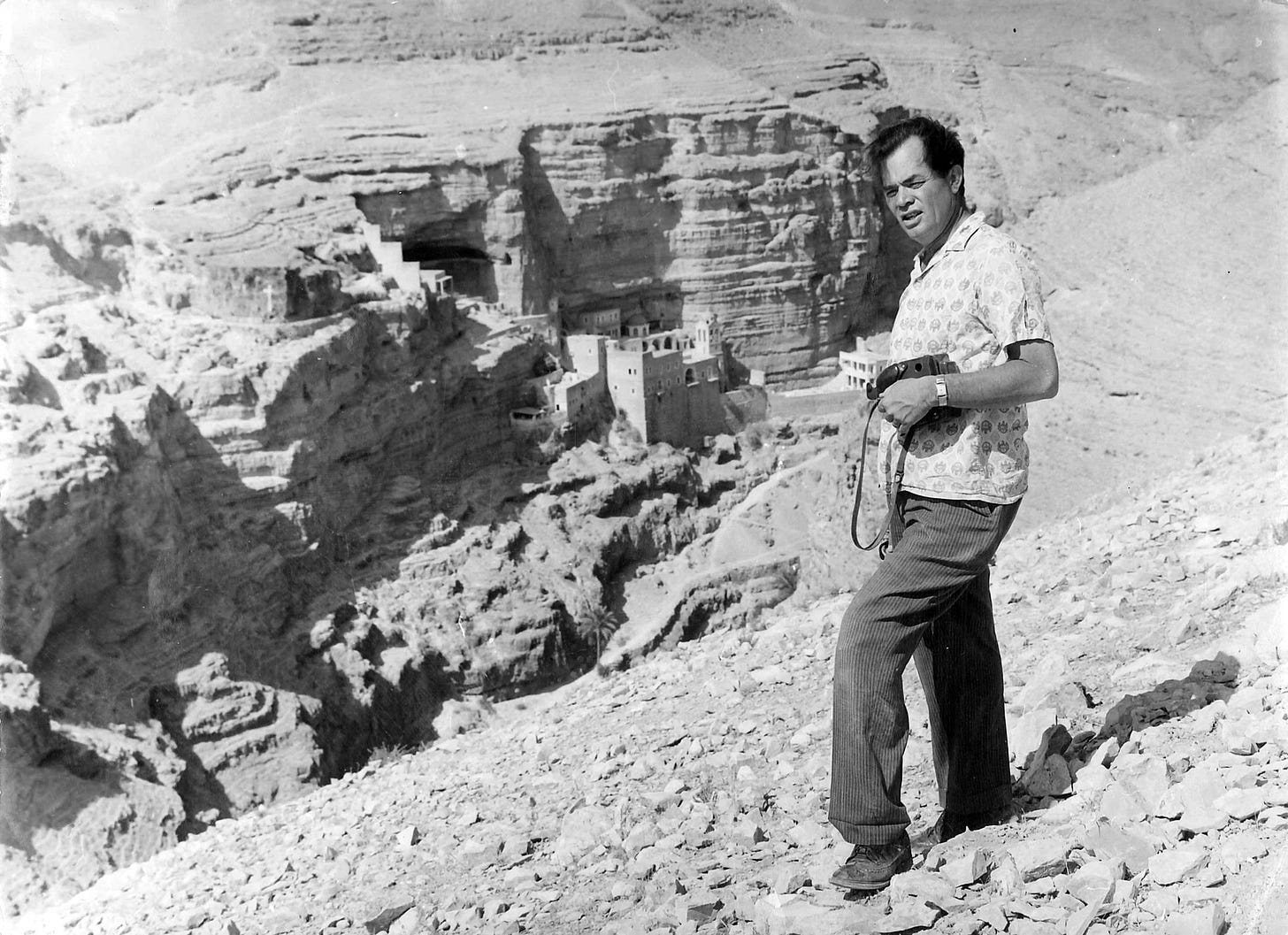

Immediately after graduating from journalism school, I hopped on a plane for Tel Aviv with an open-ended return ticket, good for a year. I spent that year hitting the mean streets (and rocky hills and deserts) of Israel, the West Bank and Gaza, Egypt and southern Lebanon.

Hoping to file some gritty dispatches from exotic, far-flung places, I met the Jerusalem bureau chiefs of both the Washington Post and Time magazine. One assignment that came my way was to write a profile of Rev. Robert Lindsey, a Southern Baptist preacher heading a burgeoning evangelical Christian enclave full of American ex-pats hoping to convert Israeli Jews to Christianity.

The piece was never published but Lindsey had a lasting impact on me that I will never forget.

Source Criticism

Lindsey was a real black sheep in the Southern Baptist Conference. His dedication to pastoring his flock in Jerusalem for 30 years led him down a winding road of Biblical “source criticism,” a scholarly approach to the New Testament not taken by most fundamentalists.

Source critics – from Rudolph Bultmann to Raymond Brown – have searched the biblical texts for clues to their original sources. These are the guys who decided Mark was the first gospel to be written and there must have been a “Q-document” containing the passages that Matthew and Luke share in common.

The gospel writers were, in essence, first-century journalists trying to piece together biographies of Jesus Christ. Not exactly what Southern Baptists mean when they proclaim the Bible “infallible,” with “God for its author, salvation for its end, and truth, without any mixture of error, for its matter.”

Lindsey had gone to seminary but was really a shoe-leather scholar. He had studied New Testament Greek down in Kentucky but learned Hebrew by living in Jerusalem. In the late 1960s, he attempted to translate the Gospel of Mark from Greek to Hebrew and it blew all his seminary notions to bits.

As he went line by line, story by story, Lindsey noticed that sometimes Mark translated effortlessly into Hebrew and sometimes it didn’t. There were many phrases that had no equivalent in Hebrew at all. He compared parallel accounts in the other gospels. The more he translated, the more the picture came into focus: Luke was the first gospel, written like a true journalist, and Mark came later, written with poetic wordplay like a rabbi.

A detailed study of the order of passages in the three gospels – and the language used – convinced Lindsey there must have been a pre-Mark gospel, a highly literal translation from a Hebrew source into Greek. The text of the Gospel of Luke is actually the most faithful to what he called the “Proto-Narrative.”

The Four Easters

Two thousand years of preaching, art and study have merged Easter stories into a big amalgam of tradition, but what if the gospels were viewed separately? Like they were four newspaper accounts of the same events? What could we detect about the sources of the stories?

In deference to Lindsey, we’ll start with Luke. Luke opens his gospel by stating, “Since I myself have carefully investigated everything from the beginning, I too decided to write an orderly account for you.”

Luke wrote that “on the first day of the week,” some women brought burial spices to Jesus’ tomb. (Jews traditionally number the weekdays 1-6, followed by Sabbath. Sunday is “first day.”) They found the stone that had sealed it rolled away, but did not find the body inside. Also from chapter 24, verses 1-8:

Two men in brightly shining clothes were suddenly standing beside them.

The men said, “Why do you look for the living among the dead? He is not here; he has risen!”

Mary Magdalene, Joanna, Mary the mother of James, and other women returned to the apostles and gave a report.

The apostles did not believe them.

Peter, however, ran to the tomb where he saw strips of linen lying inside.

Mark’s gospel has a similar account with some differences. Mark chapter 16, verses 1-8, places Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James, and Salome at the tomb, again with spices to anoint Jesus’ body. The stone has been rolled away.

They discovered a “young man dressed in a white robe” inside the tomb, sitting on the right side.

He said, “Don’t be alarmed. You are looking for Jesus the Nazarene, who was crucified. He has risen!”

The man further instructed them to tell Peter and the disciples, “He is going ahead of you into Galilee. There you will see him, just as he told you.”

So far, the firsthand sources behind the story would be Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James, and others (Joanna, Salome). Luke reports two Men in White at the empty tomb; Mark has only one.

Matthew’s version is quite different (chapter 28:1-20). Here we are told that the women – Mary Magdalene and “the other Mary” – witnessed a violent earthquake, an angel descending from heaven, rolling back the stone and sitting on it.

The Jewish temple guards were on hand, so afraid that they shook and “became like dead men.”

The angel said, “Do not be afraid, for I know that you are looking for Jesus, who was crucified. He is not here; he has risen, just as he said.”

The angel also instructed the women to tell the disciples they would see him soon in Galilee.

Jesus appeared and confirmed the angelic message, “Go and tell my brothers to go to Galilee; there they will see me.”

Matthew is also the sole reporter of a first-century false flag conspiracy theory. We are told that some of the temple guards went into the city to check in with their superiors. These chief priests were the ones who had urged the Romans to crucify Jesus in the first place. They were so concerned that the disciples might steal his body and then tell the people Jesus had risen from the dead, that they deployed guards to the tomb. “This last deception will be worse than the first” (Matthew 27:64).

So now their fears were materializing. Perhaps the guards’ version of the facts differed on the earthquake and angel details, or the chief priests didn’t believe them. In any case, Matthew reports that the elders gave the guards hush money with instructions to blame Jesus’ disappearance on his disciples. “This story has been widely circulated among the Jews to this very day,” Matthew concludes, apparently addressing a familiar counter-narrative.

Finally, let’s consider John’s gospel. Scholars have categorized the first three as “synoptic” gospels because they contain many of the same stories and language. John is a radical departure, so he gets his own category. Lindsey did not address John in his synoptic studies, but let’s see how his account stacks up.

Mary Magdalene is again a source. John doesn’t mention any other women in chapter 20. The stone had been removed but there’s no encounter with shiny men or angels.

Mary reported to Simon Peter and “the other disciple, the one Jesus loved,” that the body of Jesus was gone and she was distraught.

Peter and the other disciple ran to the tomb, with the other disciple getting there first.

He saw strips of linen lying there but didn’t go in until Peter arrived and led the way.

Peter also saw the linen strips, as well as the cloth that had been wrapped around Jesus’ head, separate from the linen.

The other disciple followed inside and “believed.”

Later, Mary Magdalene was outside the tomb, crying. She could now see two angels in white inside, seated where the body had been, one at the head and the other at the foot.

The angels asked her, “Woman, why are you crying?” Mary replied, “They have taken my Lord away and I don’t know where they have put him.”

Mary turned around to find Jesus standing there, but she did not recognize him at first. He asked her, “Woman, why are you crying? Who is it you are looking for?” Thinking he was the gardener, she said, “Sir, if you have carried him away, tell me where you have put him, and I will get him.”

Jesus revealed himself by speaking her name. She answered with “my teacher” in Aramaic, the spoken language of first-century Jews – “Rabboni!”

Mary reported all this to the disciples.

Lindsey’s Conclusion

The fact that biblical accounts don’t agree 100 percent – or are contradictory at times – didn’t bother Lindsey, a Baptist till the day he died in 1995. He saw the gospel writers as human beings inspired to set down a written record of a most amazing man.

The body of Jesus has never been found and numerous theories have been debated as to what happened that first Easter morning. Lindsey’s rejection of the notion that the gospels were fictional products of Greek-speaking Christians a century after the facts is persuasive – at least to me.

“Jesus and the stories about him reveal a Jewish figure set squarely in the middle of the Jewish context of the First Century,” he said. “The gospels are far too Jewish to reflect the ideas produced by non-Jews of any kind.”